Disability Etiquette in 3 Questions

/Because we can never have enough guides to Disability Etiquette ...

I’ve been wanting to write a post about "disability etiquette" for quite awhile. Mainly, I want to try to come up with a simple set of guidelines that covers the essentials of what we consider “disability etiquette.” First, I think we have to be clear about what “disability etiquette” is for.

Is it meant to make social interactions less annoying and humiliating for disabled people, so our everyday lives suck a little less? Or, is it designed to make non-disabled people feel more confident interacting with disabled people, so they will interact with us instead of shying away?

Obviously, it’s a little of both, and I don’t think the two goals necessarily conflict. With both in mind, let’s take a shot at a three-point guide, structured by three very basic questions I think non-disabled have about us, and that we have about how we actually want social interactions to go:

Question 1:

Is it okay to ask a disabled person about their disability?

Answer:

It depends on the situation and how well you know the disabled person. If you’re a stranger or an occasional acquaintance, it’s hard to justify asking a disabled person about the specifics of his or her disability. Even if you know them pretty well, if you’re talking about work, or your last vacation, then it’s probably awkward and inappropriate to suddenly say, “You know, I’ve always wondered, what is your disability actually called?” On the other hand, if you are a wheelchair user in the emergency room because you’re violently ill, it’s probably okay for the nurse to ask for some details, even if he or she is a complete stranger.

If you’re not sure whether you know someone well enough to ask, think of an analogy. In a similar situation and level of acquaintance, would you ask whether someone is married or has kids? Would you dig further and ask if they are divorced or widowed? The better you already know and trust someone … and the better they know and trust you … the more it’s potentially okay to ask personal questions like that, including questions about a person’s disability.

Above all, think about why you feel the urge to ask. Do you have a truly practical need to know? Are you asking because you want to know them better as a person? Or, is it just insatiable curiosity, like an itch you’re just dying to scratch? If your motivation is more like the latter, it’s a good sign you should probably leave it alone.

What’s it all about? Appropriateness.

Question 2:

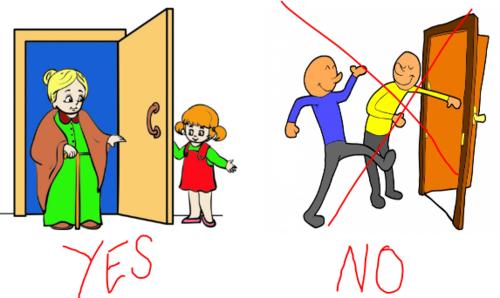

Is it okay to ask if a disabled person needs some help?

Answer:

Asking is the key. It’s almost always nice to ask. Problems arise when people dive in to help without asking, or when they ask, but then don’t listen, or overrule the answer.

If you ask a disabled person if they need help getting into or out of a building, and the answer is, “Yes!”, ask how you can help, and do what you can realistically do to help, according to the disabled person’s instructions. If the answer is, “No thank you,” or even “NO! GO AWAY!”, respect the answer, and don’t take it personally. That's right. Don't. Take. It. Personally. That can be hard to do if you’ve just been snapped at. But, if your original motivation was really to help, then it shouldn’t matter if the answer was polite, rude, or through gritted teeth. If you find yourself feeling personally offended, ask yourself whether your real priority was making the other person’s day a little easier, or was your actual goal to feel a little better about yourself. There’s nothing wrong with boosting your ego a bit by helping others, but things start to get out of balance when that’s why you offer people help.

Of course, if the disabled person takes you up on your offer, first ask how you can help and then follow the disabled person’s instructions. Don’t take “Yes, thanks” as your cue to take charge of the situation. That is exactly the sort of thing that causes many of us to resist help, especially from strangers, even when we probably really do need it. Also, following instructions is critical, even if you're sure you know what you're doing. The disabled person usually knows much better than you do how you can help them, and may also be more aware of the safest ways to do things for both of you.

What’s it all about? Control.

Question 3:

For real now, no messing around … which term should I use? Disabled Person? Person with a Disability? Physically Challenged? Special Needs?

Answer:

This one can frustrating, for sure. It seems like we are always changing our minds and can never agree even among ourselves which terms to use and encourage others to use. Given that reality, your best bet is to take a two step approach to terminology.

Start out using “disability” and “disabled” as your default terms. A lot of disabled people still don’t like “disabled” and “disability,” but it does seem to be the most universally understood and accepted term, applicable to all kinds of disabilities and across all cultures. Whether it makes complete sense to your way of thinking at the moment, it is the most widely accepted way of referring to physical or mental impairments.

If those words are accepted with no comment, you’re fine. If a disabled person objects though, and says they prefer other terms, then respect their preference, whatever it might be.

It’s worth noting that there is currently a debate going on inside the disability community between person-first language … where you say “person with a disability,” and identity first language ... where you say “disabled person” or just “disabled.” If you’re not disabled yourself, you really don’t need to worry about this. Just go with what the disabled person or people you are with seem to like better.

Above all, never lecture to a disabled person on why your preferred terms are correct, and the terms they prefer is wrong or misinformed. You might know something deeper and more significant about disability than a person who actually lives with disabilities everyday, but it's unlikely. In any case, telling a disabled person that they're doing disability wrong is just obnoxious. Don’t do it.

What’s it all about? Respect.

Is there more to “disability etiquette” than these three things … Appropriateness, Control, and Respect? I’m not sure there is.