September 26 - December 31, 2015

It is entirely possible do go out and do credible, informative accessibility ratings without having the complete ADA Accessibility Guidelines tattooed on your brain. You don’t need to know everything. You don’t have to take a hundred measurements at every place you visit, either.

It is, however, important to understand the fundamentals of accessibility in the United States in 2015. You can’t really get a proper grip on advocating accessibility without understanding:

a. What the law actually says about accessibility, and

b. What “accessible” actually means.

Which buildings are required to be accessible?

First of all, it’s not so much “buildings” as businesses that own and operate buildings or portions of buildings. Which businesses are required to have physical facilities for the public that are accessible?

- If it was built before 1992, it’s required to fix any accessibility problems to the extent it is “readily achievable.” That’s a very loose standard, open to a lot of interpretation and pleading, but it does open the door for advocacy and some basic improvements. There is no “grandfather clause” in the ADA for anyone.

- If it was built after 1992, it must be fully accessible. Full stop.

- If it was renovated, all or in part, or added to, the worked on bits must be fully accessible.

There are standards for all kinds of buildings and spaces, including schools, hospitals, hotel rooms, apartments, and recreation facilities, though the exact laws that apply to some of these kinds of places are sometimes separate from the Americans with Disabilities Act. Another complication is that the generally, the only officials who are really charged with enforcement are local building code officials, and they technically don't enforce the ADA. They enforce local building codes, which usually, (but don't always), mirror the ADA Accessibility Guidelines.

Nevertheless, basic accessibility does tend to boil down to a few important standards that apply in all kinds of situations.

What does “accessible” mean?

The first thing to say is something I think most people already know, but at times we forget. There are two ways of assessing accessibility. Is it accessible to me, with my disabilities, and does it comply with legally applicable accessibility standards. Accessibility standards aren’t perfect. They aren’t the best a business can do. They are a minimum standard. If every building complied with them, there would be much better accessibility for everyone, though still not complete.

That said, here are some basic standards to keep in your head as you rate accessibility of businesses you visit:

Doorways should be at least 32” wide. That means 32” of clear space, with nothing in the way. Make sure that when you open a door, the door itself doesn’t impede a wheelchair user’s progress in or out.

Hallways and other paths, like sidewalks, should be at least 36” wide. Again, that means clear, unobstructed space. Watch out for aisle displays in stores and things like outdoor restaurant seating that can narrow otherwise adequate sidewalks.

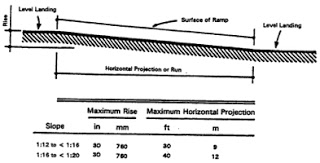

Ramps should also be at least 36” wide, and not too steep. A ramp should take at least 1 foot of horizontal distance for every 1 inch it rises. Don’t measure the ramp path itself. Measure the total height it climbs and the amount of flat space it takes up. Like this:

Ramps should also have railings on both sides. That’s both for safety, (not falling off the ramp), and so people can haul themselves up if they need to, in a wheelchair or on foot.

Entry areas near doors, areas at the top and bottom of ramps, and turning spaces inside restrooms and toilet stalls should be based on a minimum 5 foot square turning area. It’s also helpful in figuring out if other interior spaces are spacious enough or too cluttered. Like this:

Accessible restrooms and / or accessible toilet stalls should combine enough clear maneuvering space, toilet height within certain parameters, and secure horizontal grab bars behind and on at least one side of the toilet. Something like this:

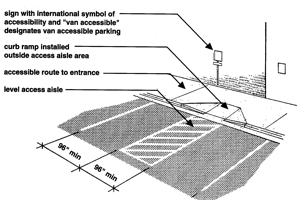

Designated disability parking should include spaces marked both on the pavement and on a vertically posted sign, and at least one adjacent access aisle. For example:

One more note ...

Whenever possible, explain the practical, real-life problems that specific barriers pose. For example, don’t just say, “The doorway is only 29” wide.” Add that this means most wheelchairs can’t get through.